Private Investigator License Update – January 2018

“How do I get my Private Investigator License?” is one of the most common enquiries we get over the telephone. This topic has been well

“How do I get my Private Investigator License?” is one of the most common enquiries we get over the telephone. This topic has been well debated and the subject of many blog posts over the years!

The below speech by Baroness Henig was made on December 7th 2017 makes reference to the licensing of our profession.

This is being called an ‘update’ in respect of Legislation but it was one speech amongst many. It was part of a lengthy debate in general for the UK and Private Investigators were only referred to specifically by Baroness Henig in her speech.

Whether or not this will put licensing back on the table remains to be seen Below is the speech for you to read through and from that you can draw your own conclusions as to any impact it may have on the likelihood of a Private Investigator License framework being developed in the near future.

At least it would still seem that self governing is off the cards, thankfully.

My Lords, I am honoured to be listed twice in this debate. I feel a bit like New York—so good they named it twice. I first draw attention to my interests as listed in the Lords register, and to the fact that for six years, from 2007 to 2013, I was the chair of the regulatory body for private security.

I commend the noble Baroness, Lady Neville-Rolfe, for introducing this important debate. I hope that she is not regretting it in any way. I strongly agree with her that proportionate regulation is very important—proportionate, that is, to the risk involved; a point made, I think, by the noble Lord, Whitty, with which I strongly agree.

I make the point about regulation being proportionate to risk because I want to speak about regulation in the private security industry, where two factors have dramatically increased the level of potential risk to the public. The first is the change in the number of private security guards, as against police officers, patrolling public space and buildings. As the numbers of police officers have consistently fallen since 2010, the numbers of security guards on the front line have risen, and they far outnumber the police as the front line of defence in our main shopping areas, streets and crowded places.

The second factor, which I need hardly emphasise, is the escalating threat of terrorist activity—to a level which is critically high in terms of risk to the public. The question arises therefore: is the basic regulation introduced to govern private security in 2003 still appropriate, effective and proportionate to the risks now entailed in 2017? The answer to that question has to be no, so what is being done about it?

It is incredible to recall that, as recently as 2010, the then Government declared their intention to abolish the Security Industry Authority—the regulatory body—and deregulate the private security industry. As a result, there was a huge outcry from the major industry bodies themselves and the businesses and their representatives, who told the Government how effective seven years of regulation had already been in raising standards and driving criminals from the sector. Commendably, they succeeded in getting the Government to change their mind. However, they also argued that regulation in the sector needed to develop, that as well as requiring individuals working in the industry to be licensed, businesses needed to be regulated and that we needed to stop unscrupulous operators lowering standards and undercutting quality operators. They argued that the four days of basic training needed to be revisited and that the stringent requirements for companies in the approved contractor scheme should be extended to all businesses.

Importantly, this was businesses not complaining about red tape but taking the lead in being forward-looking and calling for appropriate changes in regulation. The Home Office agreed with them, and the Minister for home affairs in the House of Lords—now a very senior Member of this House—told us in 2011 in this House, and told the industry, that the changes it was calling for would definitely be brought in before the end of the last Parliament. He said that business licensing would definitely happen. However, nothing happened. After this morning’s debate, I cannot help wondering whether the noble Lord, Lord Curry, and the Better Regulation Executive had anything to do with that.

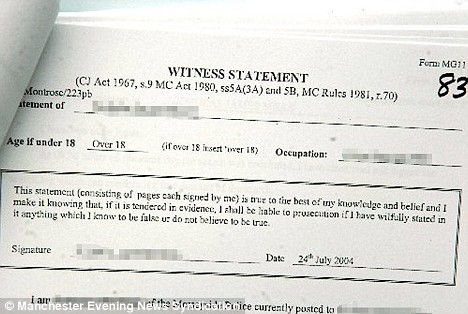

At the same time, the Leveson inquiry revealed another major weakness in the sector—the unscrupulous and often criminal activity of some private investigators. Regulation of that sector was included in the Private Security Industry Act 2001, but was postponed by the Government in 2010. After Leveson, the then Home Secretary—now the Prime Minister—promised that such regulation, which was strongly backed by the bodies representing private investigators, would be introduced as soon as possible and certainly by the end of the Parliament. Again, nothing happened.

When I raised both of these issues in this House in 2015, I was assured by the noble Lord, Lord Bates, that they would be a high priority for the new Government. Of course, they were not: that was just more false promises. Clearly we have a situation where regulation deemed essential by one government department—in this case, the Home Office—can be blocked by another, even in the face of escalating security threats and rising terrorist activity.

In 2016, a triennial review of the Security Industry Authority was completed; the report and recommendations were handed over to the Home Office. Nearly a year and a half later, we have heard nothing about this, despite Written Questions to the Home Office asking what has happened. I wonder whether the delay and the disappearance of the report have anything to do with my understanding that the independent reviewer has recommended both the licensing of private security businesses and the regulation of private investigators.

Given the risks and threats that we all now face, this is just not good enough. The security guards on the front line against terror have had basic training, and they will do their best: we have seen that in many brave actions this year. However, counterterrorism training, for example, though available, is voluntary. It is not yet an integral part of the four days of basic training that security guards receive. It should be: the Minister in charge of counterterrorism in the Home Office wants it to be. What has to happen to turn intentions such as this into action?

For some years now, the Scottish Government have insisted that security contracts in the Scottish public sector are awarded only to approved contractors, which is to say those who operate to the highest standards. That is surely appropriate to protect the public. The Government in England and Wales, not surprisingly, have not followed suit, so I am truly grateful to the noble Baroness opposite for raising the whole issue of regulation. I suggest to her that she deploy her considerable talents to persuading government colleagues in the trade department and the Cabinet Office that proportionate and effective regulation matters, that it should be taken seriously and that, without it, public safety is being endangered every day.

“How do I get my Private Investigator License?” is one of the most common enquiries we get over the telephone. This topic has been well

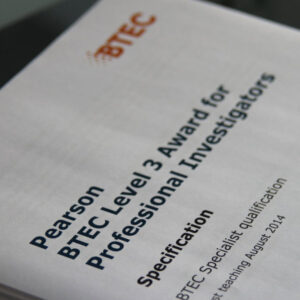

Bluemoon College has been private investigator training for over 30 years. Firstly, we delivered private investigator training for our own investigators. We also train our

Another Monday morning, raining, oppressive and miserable but my heart lifts as I head to the office. This is the time when everything seems brighter

We have now developed and launched our online process serving course – no need to wait for a workshop or having to travel to our